- Home

- About ACA

- Publications & Resources

- Programs

- Annual Meeting

- Membership

- ACA History Center

- Media Archive

ACA Early Career Scientist Spotlight-23

Personal StatementMy work aims to learn more about how post-translational modifications that occur on histone proteins interact with chromatin reader domains in proteins. We love bromodomains in the Glass Lab, and bromodomains are known to recognize lysine residues that have been acetylated. I have a funny/horrifying/turns out okay in the end story to share-I joined the Glass Lab in August 2020, and quite luckily, had some crystals that were ready to be harvested in October of 2020. In my graduate program at the University of Vermont, the first year is spent on rotations, so I had been introduced extremely briefly to crystallography at the end of my rotation in November 2019 (extremely briefly meaning looking at beautiful pictures of crystals in the Hampton Research pamphlet). So, I knew very little about the harvesting process, but had watched it a few times when others in the lab had collected their crystals, and I had even tried fishing out some older crystals for practice. I had a few wells that contained beautiful crystals-like the ones I had been looking at in the Hampton Research pamphlet, and they were ready to be harvested. I had put a lot of hard work and effort into this protein purification prep that formed these crystals, I was ready and very prepared to harvest and quickly plunge freeze a crystal from my 24-well screen even though I was wary around liquid nitrogen at the time. Everything went fairly smoothly. My PI Karen was extremely helpful and calming when I was fishing out the crystals and even though I crushed/shattered a few, we filled half of a puck with crystals from my screen. There was one very large nice-looking crystal that we were both extremely excited about that we really hoped would give us good data so we were feeling great! Everything is fine – until – it’s time to put the puck into the storage dewar. In a series of many unfortunate events, when transferring the puck filled with crystals, and that beautiful crystal from liquid nitrogen in the small freezing dewar back into the cane, we couldn’t get the puck to lock into place. Unfortunately, after much wiggling, the puck fell on the ground, the lid of the puck came off, and all of the crystals were lost – including that one extremely big and beautiful one we were so hoping to collect data on. This story doesn’t have this sad of an ending, however. We took some deep breaths and decided to persevere, like one must do in any area of scientific research, and tried harvesting again a couple of weeks later. Again, luckily for me, I had set up multiple crystal screens and found a condition for a 24-well plate that produced large, beautiful crystals. This next time we harvested, we filled an entire puck, safely got it into the cane and lowered it into the storage dewar so data could be collected. One crystal diffracted to 1.60 Å, and I was able to solve the structure of my bromodomain bound to a histone ligand (PDB ID: 7M98), that provided new ligand coordination insights which was included in a publication! Ultimately, even though we lost many a good crystal on the first harvesting day, we decided to keep moving and ended up with what we set out to do. I wanted to share this experience because now I think it’s funny and I believe it illustrates how exciting the world of structural biology is. I’m working on a different project now and it’s been much harder trying to obtain meaningful structural data, and I think about this experience often. While I may never know if that beautiful crystal would have diffracted, it’s alright and I just had to move on so that we could try other options. This perseverance paid off, and I am looking forward to perseverance in my current project to pay off as well. |

Kiera Malone

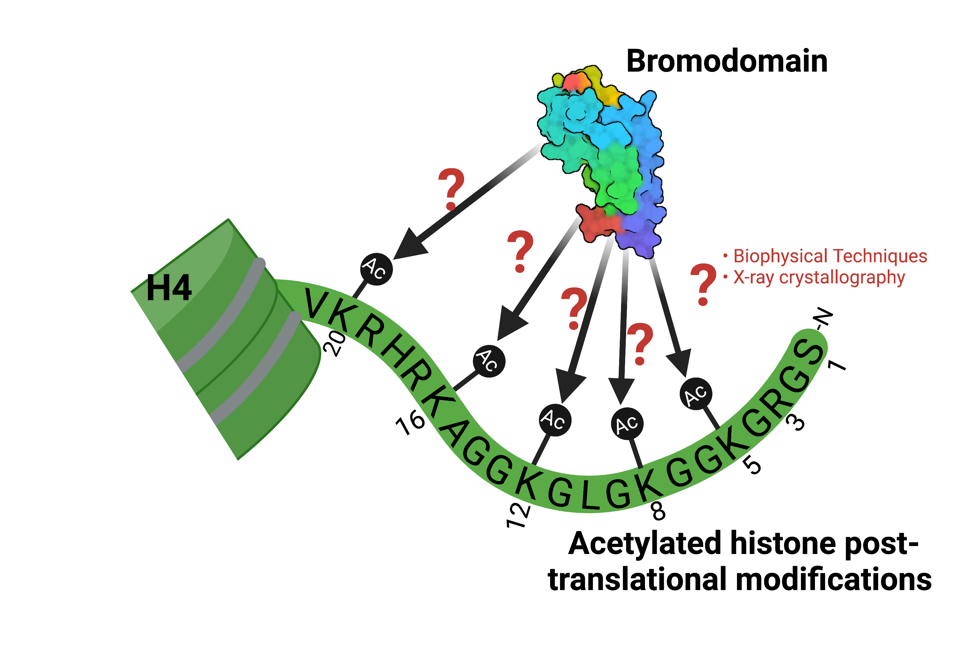

Kiera Malone To learn about how bromodomains can recognize these modifications, we use multiple methods, various biophysical techniques, and of course, X-ray crystallography in order to learn more about the coordination between protein and ligand.

To learn about how bromodomains can recognize these modifications, we use multiple methods, various biophysical techniques, and of course, X-ray crystallography in order to learn more about the coordination between protein and ligand.